Virginia

Kia ora tatou:

The portrait is one of the oldest genres in photography. You may be interested to know that, while recording the landscape was the reason photography came into being as a technology, the portrait was the economic engine that drove its development. When people realised that they no longer had to find a (very expensive) professional painter to have their portrait done, that it was now affordable, they flocked in their droves to the nearest professional photographer, to have their likeness recorded. For the first time in human history, it was possible to have an accurate record of themselves and their lives. Needless to say, average portrait painters went out of business overnight.

The portrait is somewhat of a fraught area. It carries a lot of baggage, both social and historical. In addition, there is the issue of photographing another human being. An insensitive and are un-aware approach can do a lot of damage. When we make portraits, we have immense power; the power to make our subjects feel good about themselves, or the power to destroy. Portrait photography is not an area for the psychologically jackbooted.

No wonder so few of us like having our “photo taken”...

Which brings me to the point of this post.

I had the singular honour of mentoring Virginia, as she produced a body of work for an exhibition and later for her associateship. Virginia is one of those wonderful people who is interested in everything, but especially the human condition. Her life has been a road containing more than its fair share of potholes, but she remains deeply interested in people and the lives of those around her. She is one of those wonderful human beings who are able to see beyond her own difficulties, take life by the throat and give it a really good shake. She has a real concern for others and an intuitive understanding of what makes people tick, not to mention a ferocious intellect and a razor-sharp wit. In other words, all of the things needed to make a fine portrait photographer.

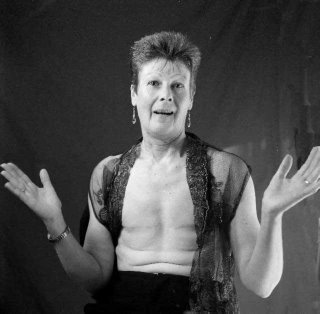

In our initial discussions, she expressed interest in making photographs of the women in a dragon boat team with which she was involved. The thing that makes this group of women so special is that they have all survived breast cancer, and the psychological trauma of the disfigurement that so often goes with it. She wanted to photograph the women and show their courage and nobility, and perhaps give them a new way of looking at what had happened.

Virginia is one of those wonderful photographers who are idea-driven, so I taught her the basics of studio photography and loaned her a Mamiya C330 6x6. We felt that the formality of using a twin-lens reflex would give her photographs the right feel. We both agreed it had to be black-and-white. We also talked about shooting angle and the importance of correct camera positioning. Because she wanted to show her respect for his subjects, she chose a fractionally lower camera angle to demonstrate this.

Then she went to work.

From time to time, she would get in touch, and we would look through what she had done. I would suggest ways in which she might refine her technique or make slight adjustments to the lighting. From the start, there was no way I could or would comment on the content of the pictures she was showing me. They were and are so extraordinarily powerful, that I was moved every time I saw them. I still am.

Needless to stay, she completed the project, and has produced a series of images which bear testament both to her own talent and commitment, but as importantly, to the extraordinary courage and fortitude of the women she has photographed.

Something special has happened here.

Ka kite ano

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home